“An end fitting for the start/ You twist and tore our love apart.” “Know that I am so close behind you that if you stretch out your hand, I think you can reach mine. Shortly beforehand he wrote to her his final farewell – a coda to the ballad that had come to define her in the wider world.

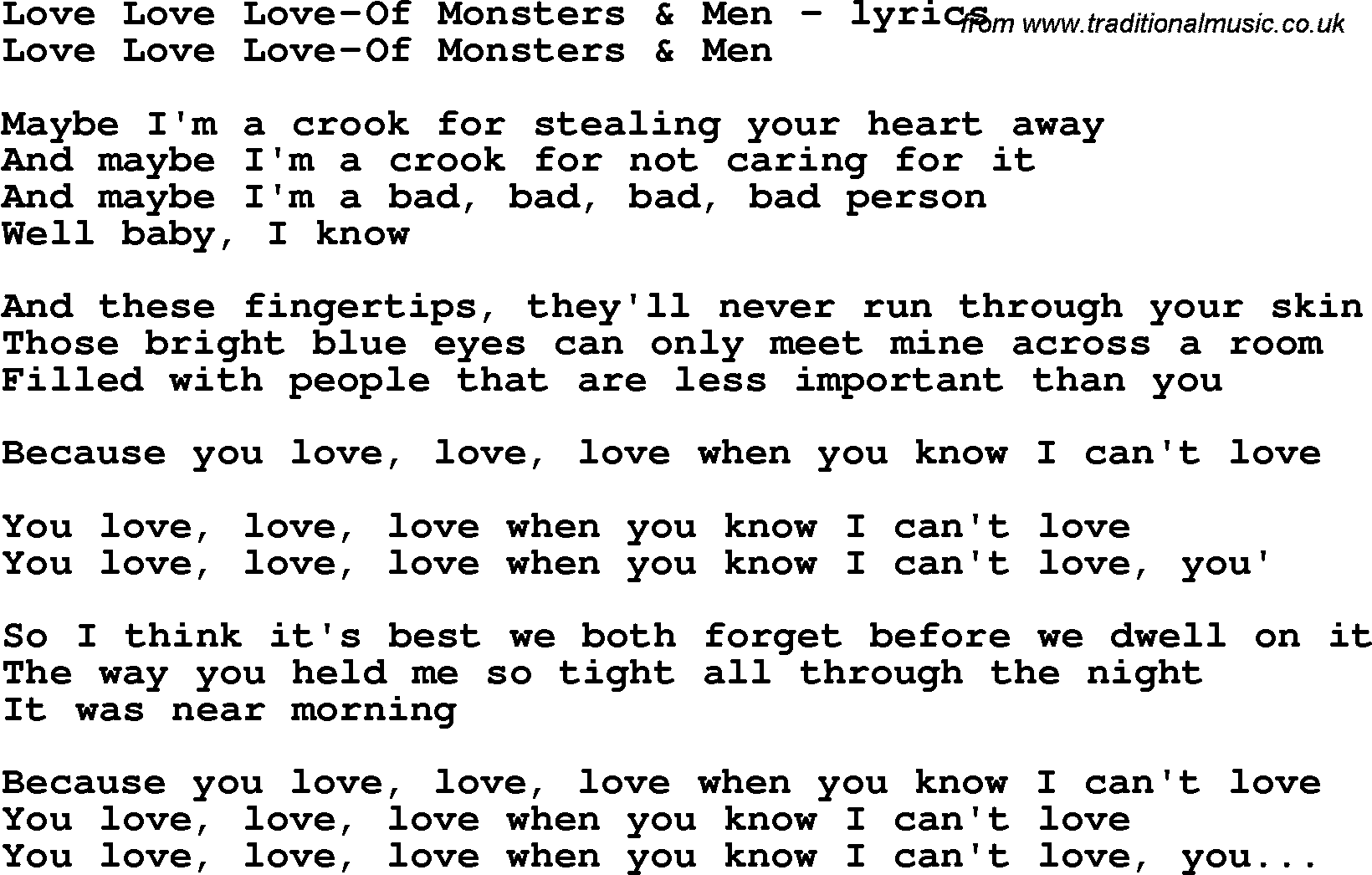

She died three months before Cohen, in July 2016. As the lyrics attest, they ultimately passed like ships in a long, sad night. “So Long, Marianne” was devoted to his lover, Marianne Jensen, whom he met on the Greek island of Hydra in 1960. You could fill an entire ledger with unforgettable Cohen lyrics – couplets that cut you in half like a samurai blade so that you don’t even notice what’s happened until you suddenly slide into pieces. “Well you know that I love to live with you/ but you make me forget so very much/ I forget to pray for the angels/ and then the angels forget to pray for us.” But, as Murphy desperately reels off all his cutting edge influences, it’s the seam of genuine pain running through the lyrics that gives it its universality. Long before the concept of the “hipster” had gone mainstream, the 30-something James Murphy was lamenting the cool kids – with their beards and their trucker hats – snapping at his heels.Ĭoming out of his experiences as a too-cool-for-school DJ in New York, the song functions perfectly well as a satire of Nathan Barley-type trendies. One of the best songs ever written about ageing and being forced to make peace with the person you are becoming. It’s one of the most coruscating anti-love songs of recent history – and a reminder that, Mumford and Sons notwithstanding, the mid-2000s nu-folk scene wasn’t quite the hellish fandango posterity has deemed it. Haunted folkie Marling was 16 when she wrote her break-out ballad – a divination of teenage heartache with a streak of flinty maturity that punches the listener in the gut. “Lover, please do not/ Fall to your knees/ It’s not like I believe in/ Everlasting love.” “You might just be a black Bill Gates in the making,” she muses, but then decides, actually: “I might just be a black Bill Gates in the making.” In a society that still judges women for boasting about their success, Beyonce owns it, and makes a point of asserting her power, including over men. The lyrics reclaim the power in her identity as a black woman from the deep south and have her bragging about her wealth and refusing to forget her roots. Beyonce had made politically charged statements before this, but “Formation” felt like her most explicit.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)